In my last article, I laid out the case for why we should make empathy a core tenet of our practice as teachers. Training our students in empathy (and intentionally practicing it ourselves) can improve test scores, counteract the effects of trauma, and model positive relationships for students who may not always have clear guides to look to.

That was the why. Now, let’s talk about the how.

A classroom culture rooted in empathy is not something that just happens. And it does not spring forth solely from the efforts of some miracle-working “super teacher” (a la Freedom Writers or Dead Poets Society). Truly empathetic spaces are the result of lots of small but intentional choices, habits, and behaviors that add up over time.

With that in mind, I would argue that we should approach developing empathy in the same way we approach teaching any other skill. We do some backward mapping: start with the end in mind and set up practices and procedures to help our students (and ourselves) get there.

So What Does an Empathetic Classroom Look Like?

Positioning empathy at the center of our classrooms and curriculum doesn’t have to involve a complete overhaul of our teaching. The first step might be to simply reinforce what you’re already doing.

Reading for Empathy

If empathy is a muscle, then reading is the best exercise. As novelist Amy Tan writes, when we “read about the lives of other people” we “inhabit their lives” and “feel what they’re feeling.” Neuroscience supports Tan’s description. Studies have shown that while reading fiction, our brains respond to the story in the same way they would to real-world stimuli. The empathy we feel for characters actually bolsters the neural pathways that help us care for real people.

By simply sharing narratives with our students, we are helping them learn what it feels like to climb into someone else’s skin and walk around in it, as Atticus Finch suggests in To Kill a Mockingbird. This offers us a unique opportunity. We can intentionally choose texts that connect students with characters of very different backgrounds, stretching their capacity for empathy and expanding their worldview.

My 10th grade English course is centered around three memoirs of teenagers growing up in turbulent circumstances. A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah focuses on the author’s experiences as a child soldier in Sierra Leone. Night by Elie Wiesel describes the author’s years in a concentration camp. Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi chronicles the author’s coming of age during Iran’s Islamic Revolution. Throughout the semester, I regularly ask students to think about how they see themselves in these teenage characters, and I ask them to draw comparisons between the stories. By the end of this sequence, students consistently express their realization that people all around the world are really just like them.

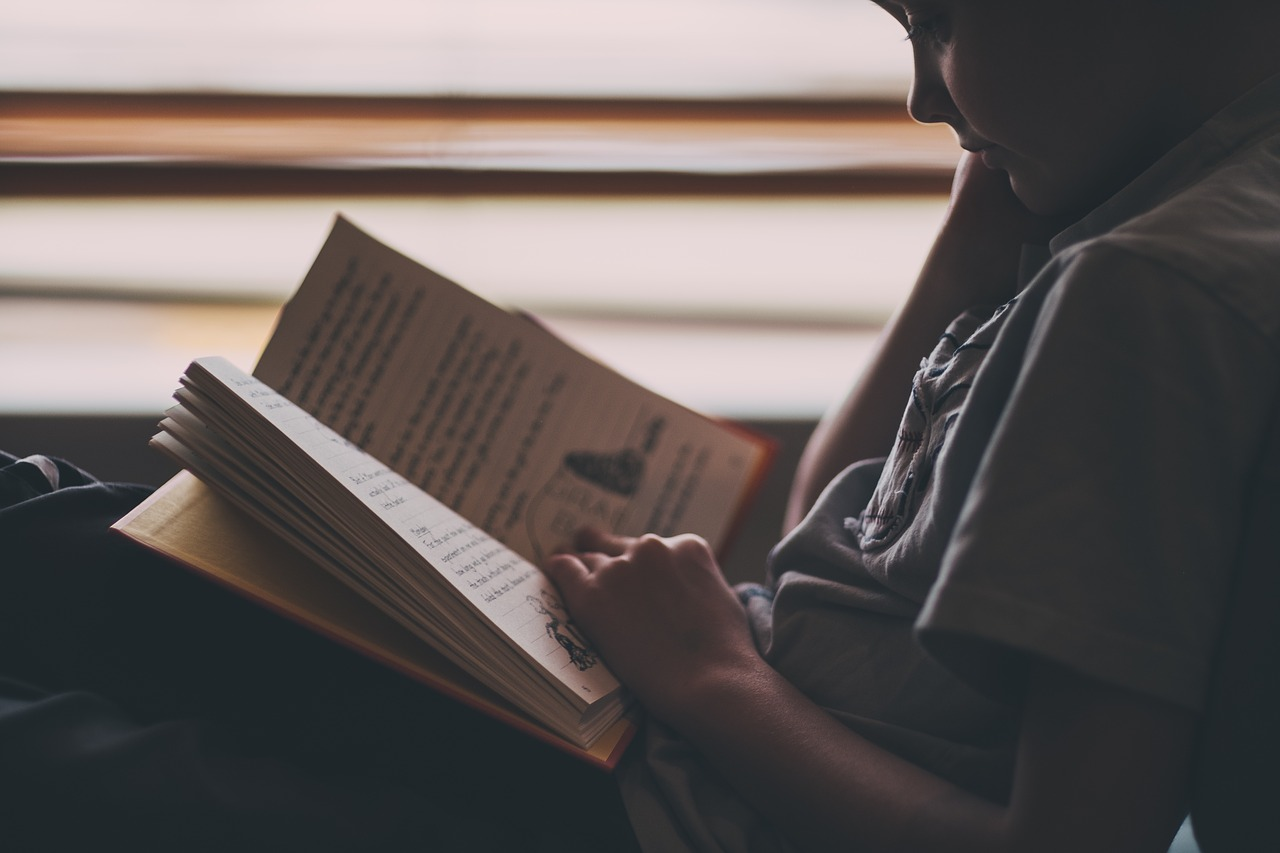

Screenshot of student response to a discussion question on Persepolis

Screenshot of student response to a discussion question on Persepolis

Collaborative Learning Activities

*A slide I use when introducing Socratic Seminar expectations to my students

*A slide I use when introducing Socratic Seminar expectations to my students

Tasks in which students work towards a common goal are another great form of empathy strength training. When students buy into the idea that their success depends on the efforts of others, they begin to see each other not as competitors but as sources of support.

Jigsaw activities are great for this. In a Jigsaw model, each student in a group is assigned one piece of a larger puzzle – perhaps one section of a text or part of an author’s background. Students become experts in their specific content and then present their findings to the group. Groups then answer questions or respond to a writing prompt that requires them to synthesize what they learned from each other.

In my classroom, Socratic Seminars are another way I cultivate connections between students. When I lay out the goals of these discussions, I emphasize our need for each other’s perspectives to more fully understand the text. I directly teach active listening and require students to reflect on others’ comments. (See an example of a discussion contribution and listening guide I use here.) Over the course of a semester, these whole-group discussions naturally yield powerful moments of connection as students share ways the text relates to their own lived experiences.

Routines and Structures

When you’re ready to branch out, consider adding a new class routine or structure that creates a recurring opportunity for empathy. As described in CASEL’s Signature Practices playbook, Welcoming Inclusion Activities provide excellent chances for teachers to invest relationally and for students to support and acknowledge each other. Throughout this year of remote and hybrid classes, I’ve often started class by asking students to share one highlight from the week or one thing they are looking forward to via the Zoom chat feature. We scan these comments as a group, celebrating the good things going on in each others’ lives.

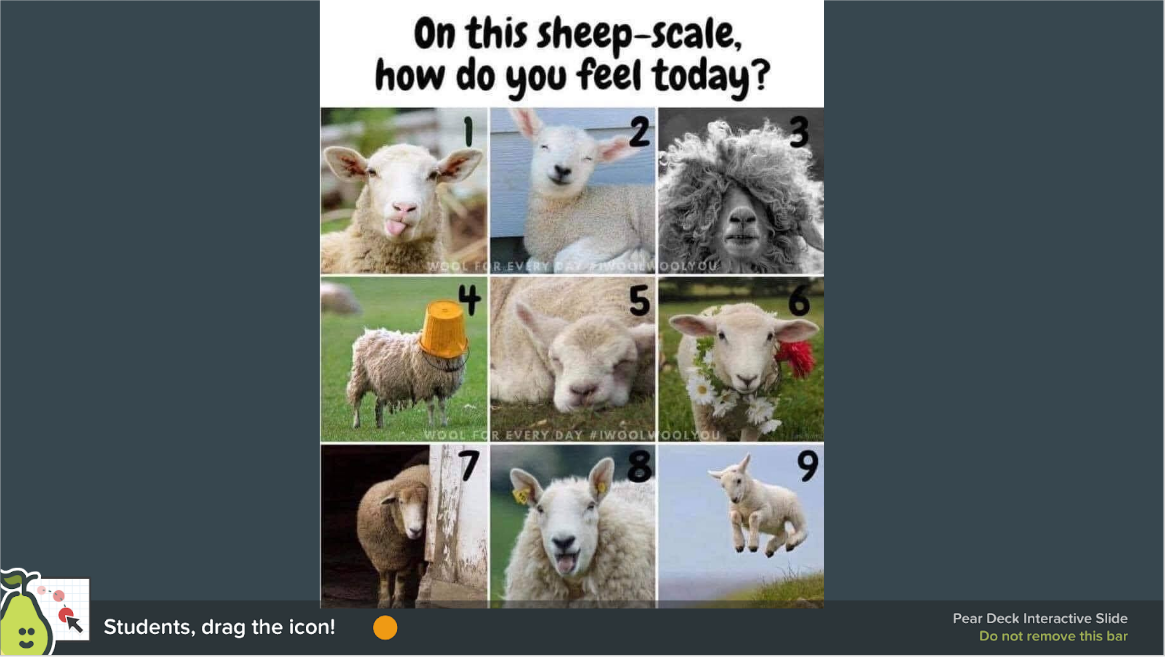

Daily or weekly feelings check-ins are a popular structure for helping students name and connect with their own emotions. This year, many of my colleagues have been using picture-based check-in boards as the first slide of their daily Powerpoint or PearDeck.

*Example of Pear Deck check-in board from one of my colleagues

*Example of Pear Deck check-in board from one of my colleagues

Before Covid-19, I used to walk around with a pad of sticky notes while students were taking tests. I would write one quick note of gratitude or praise to each student – “Thanks for always making me laugh” or “Awesome comments yesterday” – and then just stick the note to their desk. Often, much later in the semester, I would notice that students kept these post-its somewhere in their binder.

This strategy could be expanded into a routine for the whole class. Perhaps every Friday, students get two sticky notes and are asked to write a message of gratitude or praise for someone in the room. Maybe there’s a permanent bulletin board in the room – or a Google Jamboard or Padlet online – where students can continually add shout-outs and Thank-Yous for each other.

However, you choose to weave empathy into your lessons and practice, remember that it’s less about the success of anyone’s activity and more about the cumulative impact of daily interactions over time. If students feel cared for in your classroom that is going to make a difference – and the ripple effect of that difference may be more powerful than we can imagine.